On this day in 1863, Princess Alexandra of Denmark, eldest daughter of the heir to the Danish throne, married Prince Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales.

Alexandra had been considered a potential bride for the Prince of Wales, or Bertie as he was known, as far back as 1858, when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert first began considering their son’s future bride. She was not their first choice due to ongoing tensions between Denmark and Prussia over Schleswig-Holstein, but the potential German brides suggested by his parents were all rejected. The couple met for the first time in September 1861, in a meeting arranged by Bertie’s elder sister, Princess Victoria. They seemed to get on, and Bertie did express some interest, but he remained non-commital when pressed on the subject of marriage by his parents. Following the death of his father in December, 1861, and seeking to please his mother who, in part, blamed him for his father’s death, Bertie proposed to Alexandra on their next meeting, which was at the Palace of Laeken in Belgium. They became engaged on 9th September, 1862.

The below engagement portrait was taken by Ghémar Frères, photographer to Leopold I, King of the Belgians. In it, Alexandra is wearing an informal day dress with a striking Greek key braid trimming at the hem, and a ‘Zouave’ style short jacket edged in lace or embroidery. The prince has on a velvet lounge jacket and check trousers.

Their engagement was officially announced in November 1862 and the wedding date set for 10th March the following year. This left a relatively small window of time for Alexandra’s dress and trousseau to be arranged.

After the engagement, Alexandra spent an extended period of time in England to help her to become better prepared for the life she was marrying into. At this time, Queen Victoria was still in deep mourning for her husband, and so was not overly involved in helping Alexandra plan for her forthcoming wedding. Instead, she was helped with arranging her trousseau by Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge (whose daughter, Mary, would go on to marry George V). Mary Adelaide was the first cousin of Alexandra’s mother, Louise of Hesse-Kassel. They met up during a visit Alexandra made to Windsor and Mary Adelaide recorded it in her diary:

“Darling Alix too over-joyed at meeting to speak. Later played in Alix’s room en souvenir de Rumpenheim; then accompanied her through the state rooms.”

(The ‘Rumpenheim’ mentioned was a castle on the banks of the Main river in the German city of Offenbach am Main, where members of the Hesse-Kassel family would holiday during the summer.)

Alexandra was, however, careful to see Queen Victoria’s approval on all important aspects of the trousseau’s compostion – particuarly as her future mother-in-law was funding the majority of the expenditure.

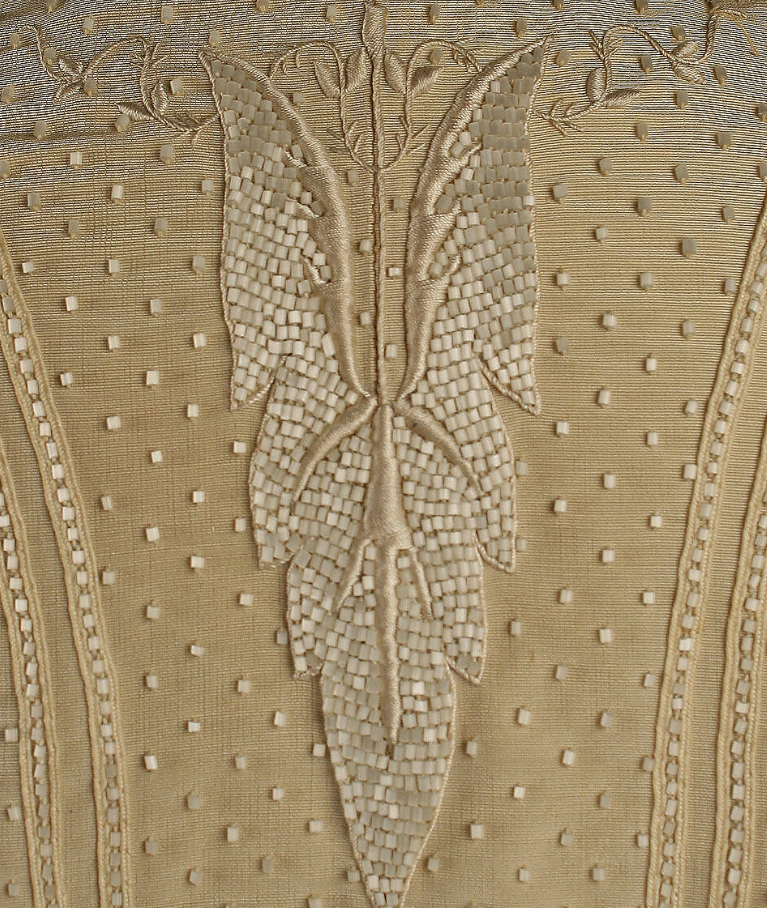

The larger part of the trousseau was made in London from British and Irish materials. The lingerie, however, was prepared in Denmark. Some garments from the trousseau do still survive – the below mantle is one such item. Made by Dieulafait & E. Bouclier, ca. 1863, of white faille silk and decorated with beadwork and fringing.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Once completed, part of her trousseau was actually put on display to the people of Copenhagen. On 26th February, 1863, The Danmark of Copenhagen gave this description:

“The bridal garments of Princess Alexandra have attracted great notice here. Their fabrication has been entrusted to Mr. Levysohn, of this city, and have been exhibited to the fair sex in his establishment in Kjobmagergade. Finer specimens of needlework will not easily be found. The stitches are so fine and the work so delicate, that they have excited universal admiration. No machine has been employed. On each piece has been embroidered her Royal Highness’s initials, below the English crown, and this alone has given 600 such embroideries. The time allowed being so short, several hundred persons have been employed, but the greatest accuracy and uniformity has been obtained. The handkerchiefs have been ordered in Paris, and are masterpieces in their kind, the embroidery being remarkably tasteful and beautiful. The English crown, from its peculiar shape, has offered various difficulties, but they have been triumphantly overcome. Only a few of the robes were exhibited, some being too delicate to bear any handling. Articles of this kind more glaring and costly might easily be obtained, but certainly nothing more quietly and fittingly appropriate as perfect specimens of what the needle can accomplish.”

Other examples of the craftsmanship in her trousseau can be seen below. The first is a mantle made by Jays Ltd (London). It is of white faille silk with insertions and vandyke borders of guipure lace; trimmed with silk cording at the neck. The second, a lambswool driving coat, with wide borders and deep collar of white lambswool; trimmed with gold braid and frogs, and lined in light yellow taffeta.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As for the wedding dress; initially, she was gifted with a beautiful gown of Brussels lace by King Leopold I of the Belgians, who was Queen Victoria’s uncle. However, as with her own wedding, the queen was insistent that the dress should be British made. So the commission was given to Mrs James, an established court dressmaker from Belgravia, London.

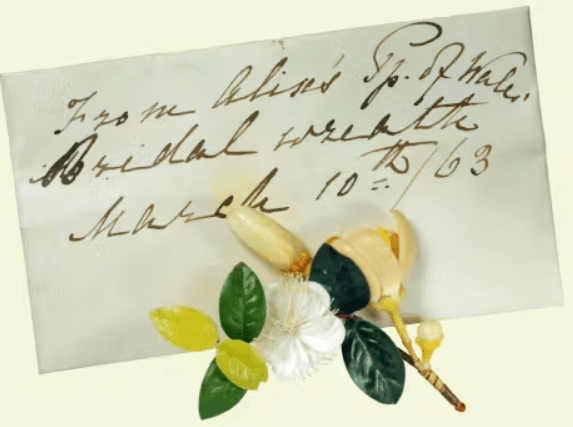

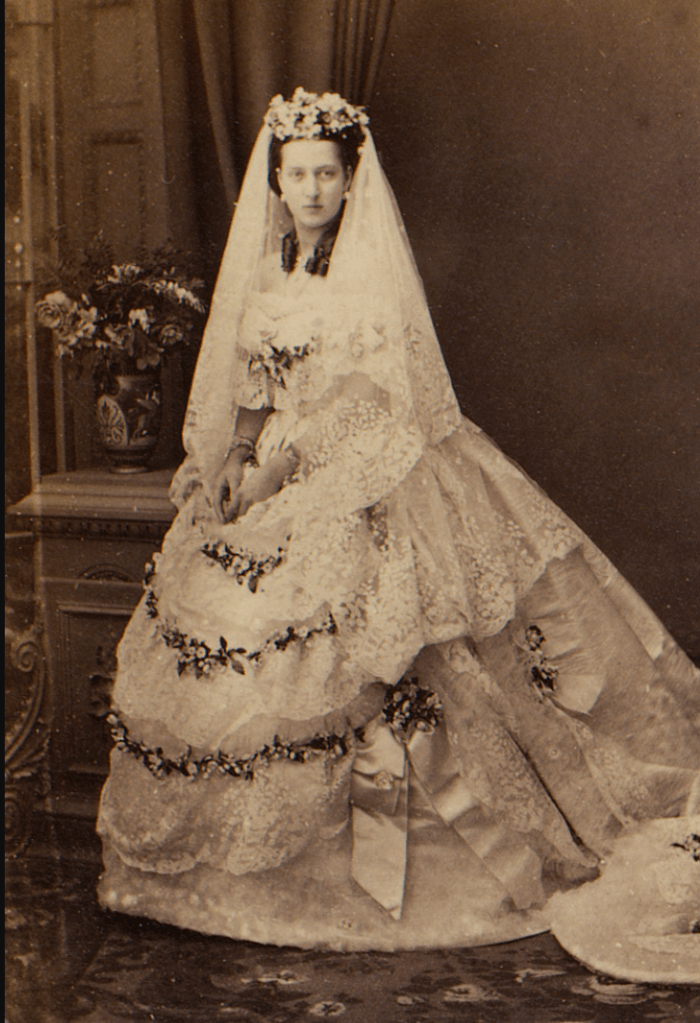

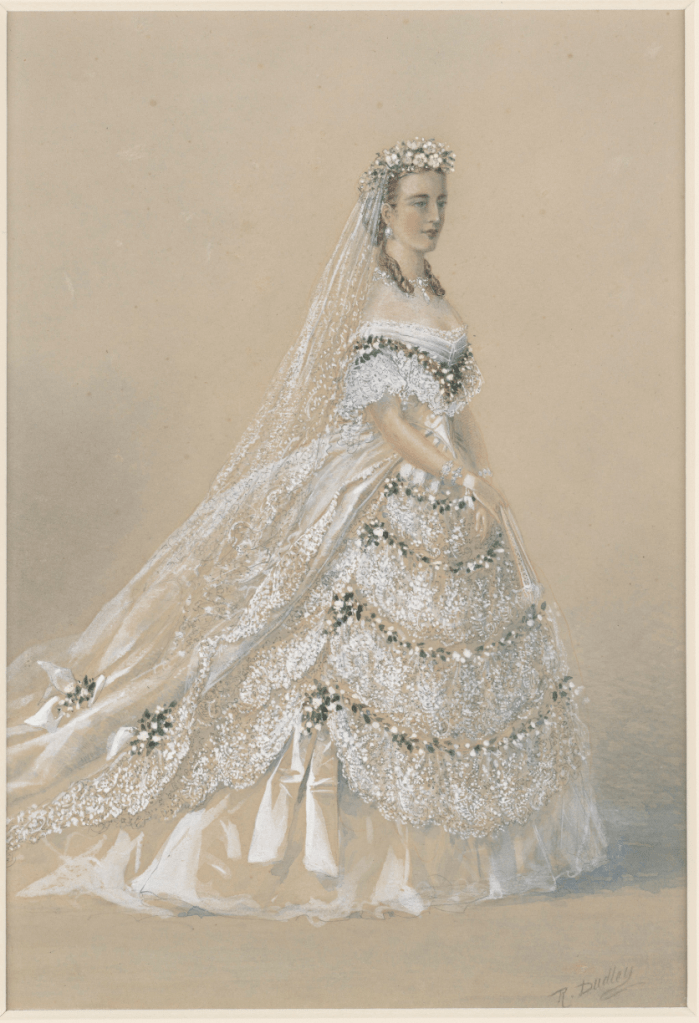

The dress was made of ivory silk satin (from Spitalfields), and was trimmed with orange blossoms, myrtle, puffs of tulle and four deep, Honiton lace flounces. It also had a 21 foot train made of silver moiré, that was carried by Alexandra’s eight bridesmaids. The flowers that adorned the dress and made up Alexandra’s headdress were artificial; a sprig of which was saved carefully by Queen Victoria.

The Honiton lace was the responsibility of Messrs. John Tucker and co of Branscombe, Devon, and the lace design was the work of Miss Mary Tucker, daughter of the family. The pattern consisted of festoons of cornucopia, filled with rose, shamrock, and thistle. As well as the dress, the lace pattern was used for Alexandra’s veil, and also as trimming on her train.

The Court Circular at the time gave a vivid and detailed description of the bride’s attire:

“The dress of the Princess Alexandra was a petticoat of white satin trimmed with chatelains of orange blossoms, myrtle, and bouffants of tulle with Honiton lace; the train of silver moiré antique trimmed with bouffants of tulle, Honiton lace and bouquets of orange blossom and myrtle; the body of the dress trimmed to correspond. Her Royal Highness wore a veil of Honiton lace, and a wreath of orange blossom and myrtle. The necklace, earrings, and a brooch of pearls and diamonds, which were the gift of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales; riviere of diamonds, given by the Corporation of London; opal and diamond bracelet given by the Queen; diamond bracelet given by the ladies of Leeds; and an opal and diamond bracelet given by the ladies of Manchester.

The bouquet was composed of orange blossoms, white rosebuds, lilies of the valley, and rare and beautiful orchideous flowers, interspersed with sprigs of myrtle, sent specially from Osborne by command of the Queen; the myrtle having been reared from that used in the bridal bouquet of H.R.H. the Princess Royal. The bouquet was supplied by Mr. J. Veitch. The lace for the wedding dress of H.R.H. the Princess Alexandra was of Honiton manufacture, and was designed and executed by Messrs, John Tucker and Co. of Branscombe, near Sidmouth. It was composed of four deep flounces of exquisite fineness, nearly covering the dress, with lace for the train; veil and pocket-handkerchief en suite. The design (made by Miss Tucker) is a sequence of cornucopia, filled with rose, shamrock, and thistle, arranged in festoons, and interspersed with the same national floral emblems. Too much praise cannot be given to Messrs. Tucker and Co. for their skill and attention in the execution of this order.”

A short time after the wedding, Princess Alexandra arranged for her dress to be altered by another dressmaker, Mme Elise, and made into an evening gown to be worn again – possibly the result of her frugal upbringing and limited trousseau. Which is why the dress, as we see it now in the Royal Collection, looks very different to the vivid descriptions and images of the time. The lace flounce on the bodice remains, but those from the skirt are gone, and it appears a new skirt was made from the fabric of the train. The alternations were made so promptly, that when William Frith, who was working on a commission from Queen Victoria to paint the official portrait of the ceremony, asked to view the dress again to ensure the accuracy of his work, he was told that it had already been altered. He described working from photographs as “the most unsatisfactory process“.

One final interesting fact about the dress comes from Dr Kate Strasdin, who examined the dress extensively as part of her research for Inside the Royal Wardrobe: A Dress History of Queen Alexandra. She noted that “a broad band of roughly cut lace had been attached to the centre front interior lining of the skirt. It was not a length of the Honiton lace which was so profuse elsewhere on the dress, but was rather a band of fine Brussels lace, distinct by its stylised flower motifs.” With no obvious purpose to this piece of lace, we can speculate (although we can never be sure) that this is a part of the gown she was gifted but not allowed to wear – perhaps a small act of rebellion on her part against her mother-in-law’s strictures.

Queen Alexandra’s wedding dress is a stunning piece of history. Do you have a favourite royal wedding gown? Or is there another bridal look you’d love me to explore? Let me know in the comments! And if you enjoy royal fashion history, don’t forget to subscribe for more.