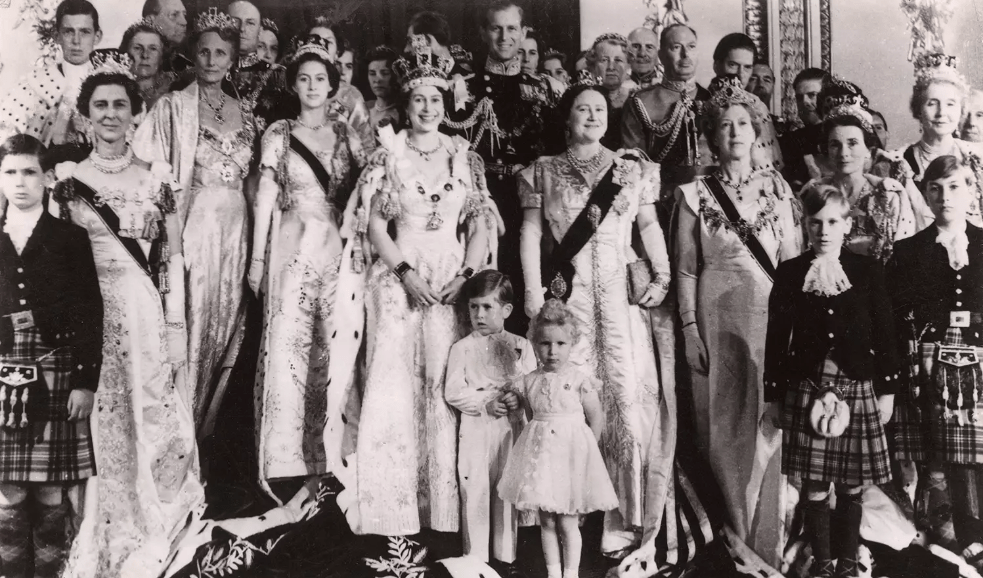

On 2 June 1953, the world watched in awe as Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in Westminster Abbey. At just 27 years old, she stood at the centre of a ceremony steeped in a thousand years of tradition – a glittering pageant of symbolism, sanctity, and sovereignty. Her coronation was the first to be broadcast on television, allowing millions around the world to witness the splendour from their living rooms.

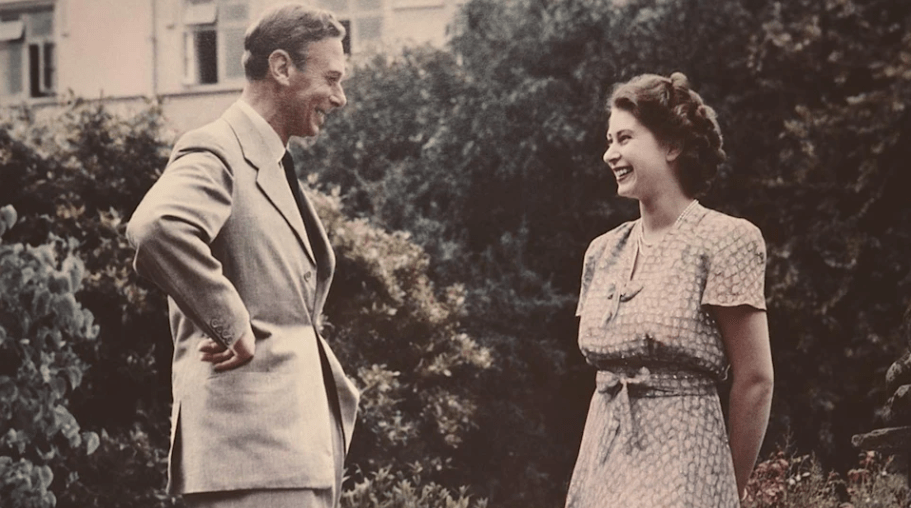

But, as is usually the case with these things, the road to the Abbey began in solemnity; her reign born not in celebration but in sorrow. For, on 6 February 1952, while on royal tour in Kenya, Princess Elizabeth received word of her father’s death. King George VI had passed away in his sleep at Sandringham at the age of 56, and his daughter, then just 25, was now Queen.

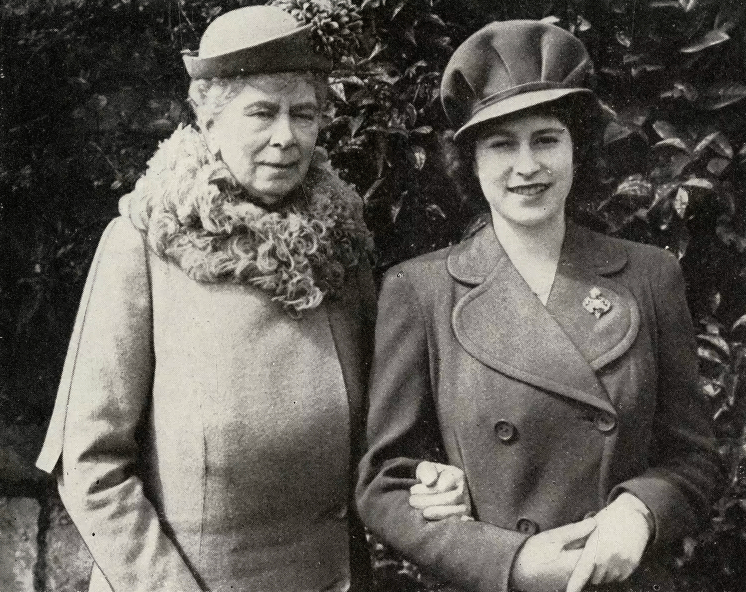

Adding to the sense of generational shift was the death of her grandmother, Queen Mary, only ten weeks before the coronation. A towering royal figure in her own right, Queen Mary had been deeply involved in court life and supported the young Elizabeth’s preparation for queenship. She made it known before her passing that the coronation should not be postponed on account of her death, underscoring the commitment to duty that characterised her long life.

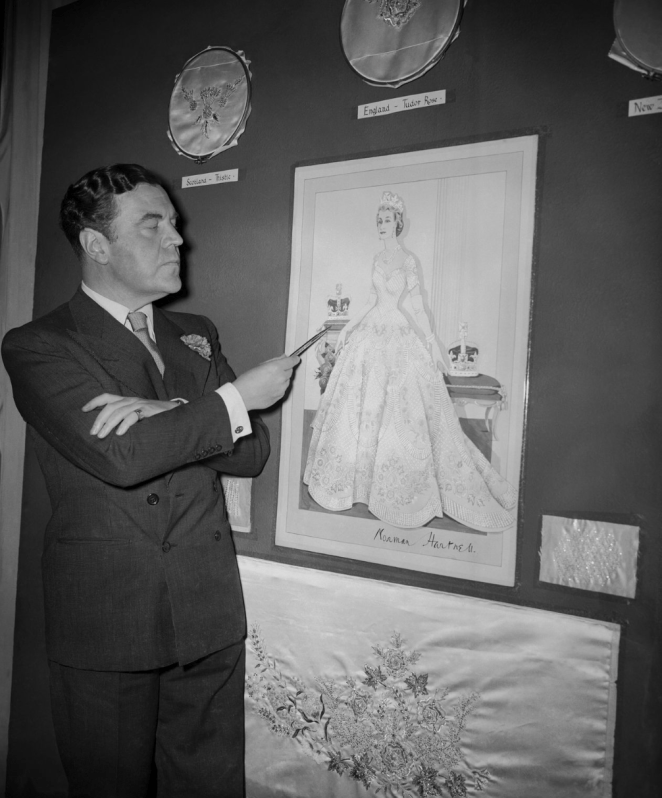

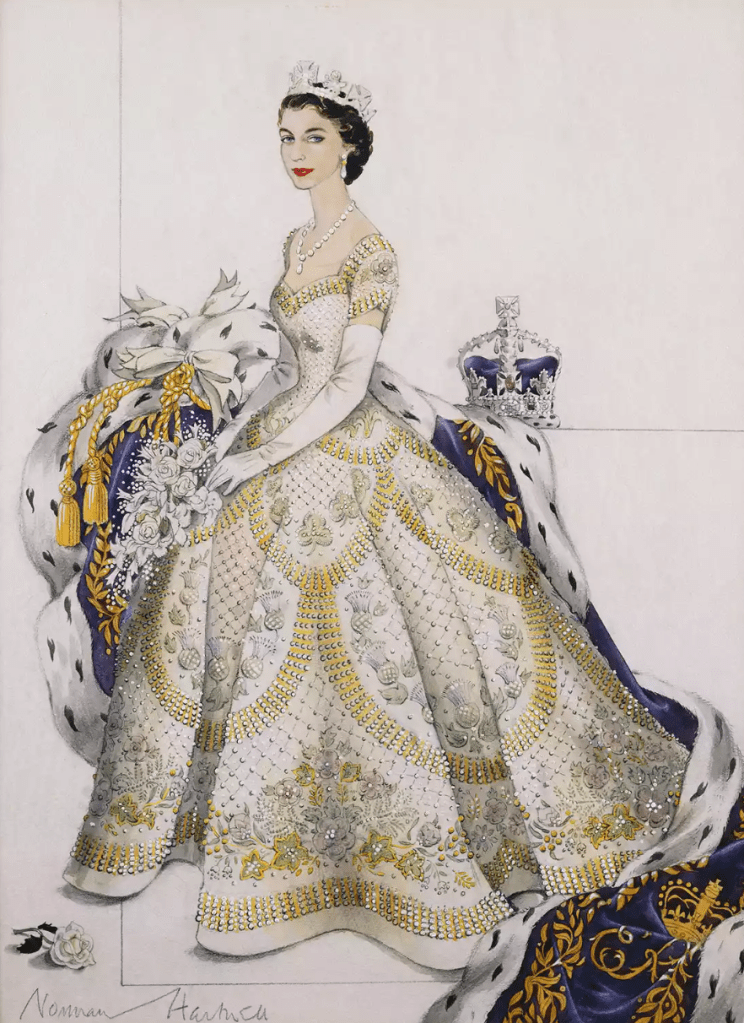

The coronation was planned for 2nd June, 1953, at Westminster Abbey. For this most sacred occasion, Queen Elizabeth II turned to the trusted couturier who had dressed her for her wedding in 1947: Norman Hartnell. Known for his opulent style and impeccable embroidery, Hartnell viewed the commission of the coronation dress as the crowning moment of his career. He called it “the greatest and most honourable commission I have ever received.”

With the gown ordered in October 1952, Hartnell went to work straight away. He presented no fewer than eight separate designs for Her Majesty’s consideration.

The first dress suggested was a simple design, similar to the one worn by Queen Victoria at her coronation. The next, a sheath gown with gold embroidery. The third was a crinoline style dress, similar in style to those he created for the new Queen Mother. The fourth, white satin, embroidered with the Madonna and arum lilies, and encrusted with pearls. The fifth was more colourful, with violets, roses and wheat embroidered across the fabric. The sixth was again white satin, this time with an oak leaf motif in fold, silver, and copper embroidery. Seven, had the Tudor Rose of England emblazoned in gold tissue on the stark fabric. And finally, number eight, similar to the last, but this time utilising the floral emblems of Great Britain.

The Queen opted for number eight, with the proviso that more colour should be used, and the emblems of the dominions should be used alongside those of the home nations.

There was a brief hiccup when the Garter King of Arms learnt of Hartnell’s plan to replace the traditional leek of Wales with the more elegant daffodil, but he was firmly told this could not be done, and thankfully acquiesced.

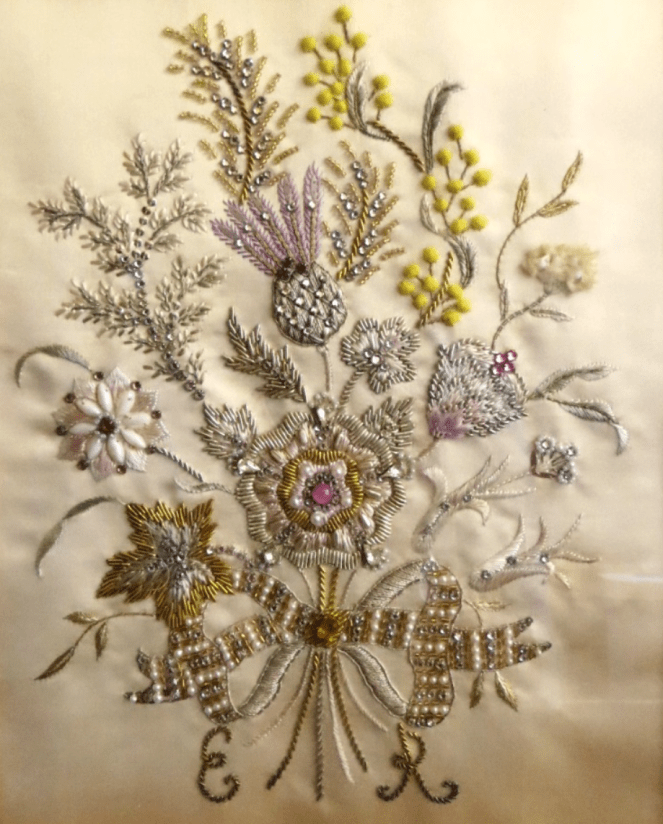

The final design was presented to the Queen at Sandringham and duly approved. It was a white duchesse satin gown with a fitted bodice, sweetheart neckline, and full flared skirt. It was densely embroidered in gold and silver thread, with accents of seed pearls, crystals, sequins, and coloured silks. It took a team of six embroideresses almost 3000 hours over nine weeks to complete the design, and, when finished, the entire gown tipped the scales at around 13 pounds (6 kilograms).

Every emblem was painstakingly researched and rendered with botanical accuracy; Hartnell reportedly consulted the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew to ensure the forms were correct. The final version featured the Tudor rose, Welsh leek, Scottish thistle, and Irish shamrock. But alongside these familiar emblems, were the Canadian maple leaf, the silver fern of New Zealand, the Australian wattle flower, the South African protea, the lotus flower of India, the Lotus flower of Ceylon, and the three emblems of Pakistan: wheat, cotton, and jute.

In a quiet, superstitious flourish, a small four-leaf shamrock was hidden among the embroidery on the left side of the skirt – positioned so that the Queen’s hand might rest upon it. It was included for good luck, a subtle symbol that belied the solemnity and weight of the moment.

Hartnell later reflected that “I felt that the dress should be so designed that it would remain ageless. I wanted it to be something that would stand as a historic document, yet never appear old-fashioned.” And so it has.

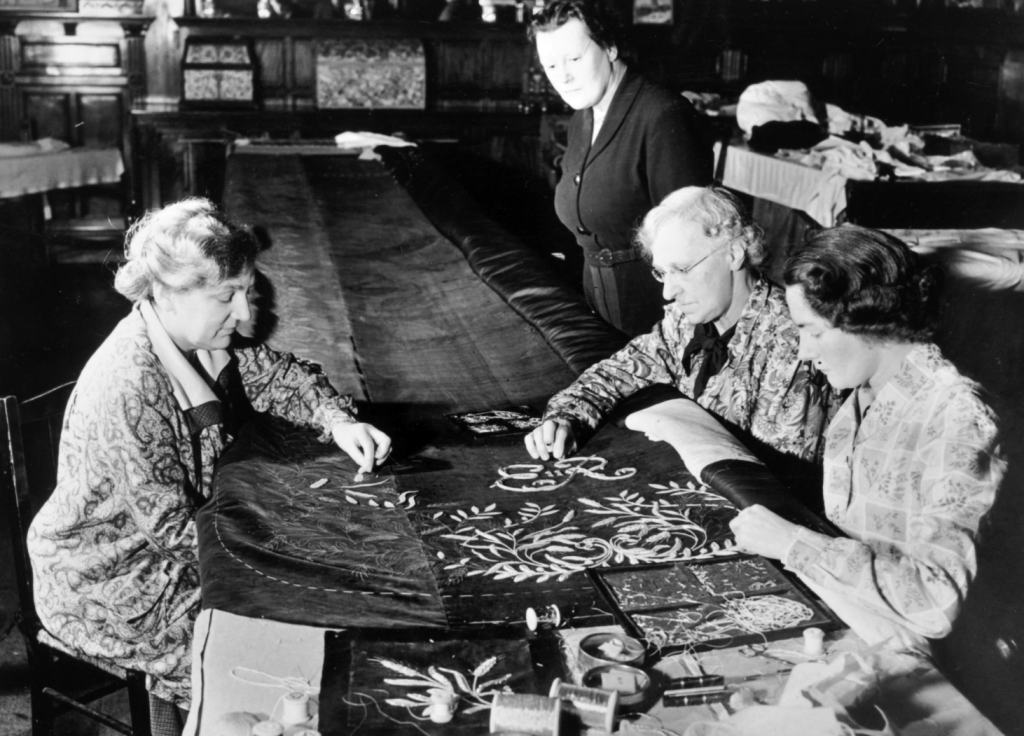

After the crown was placed upon her head, Elizabeth II departed Westminster Abbey wearing the Robe of Estate – a spectacular 21-foot train of rich purple velvet, edged in Canadian ermine. It was created by Ede and Ravenscroft, and then The Royal School of Needlework was tasked with completing the stunning embroidery. According to their website:

The Royal School of Needlework completed the embroidery on the robe in a total of 3,500 hours from February to April 1953. The work was carried out by 12 embroiderers, in shifts from 7am to 10pm each day including weekends. The work was embroidered using huge wooden embroidery frames which are still used by our Embroidery Studio.

Once completed, the motifs shimmered subtly with movement, an effect achieved by alternating textures and stitch directions – a truly impressive feat of artistry.

Both the coronation dress and the Robe of Estate now form part of the Royal Collection. They are rarely seen by the public but have appeared in a handful of exhibitions, most notably during Her Majesty’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations.

The dress did not go straight into the collection, however. After her coronation day, the Queen went on to wear this stunning gown when she opened parliaments in New Zealand, Australia, and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1954, and then again in 1957 on a state trip to Canada:

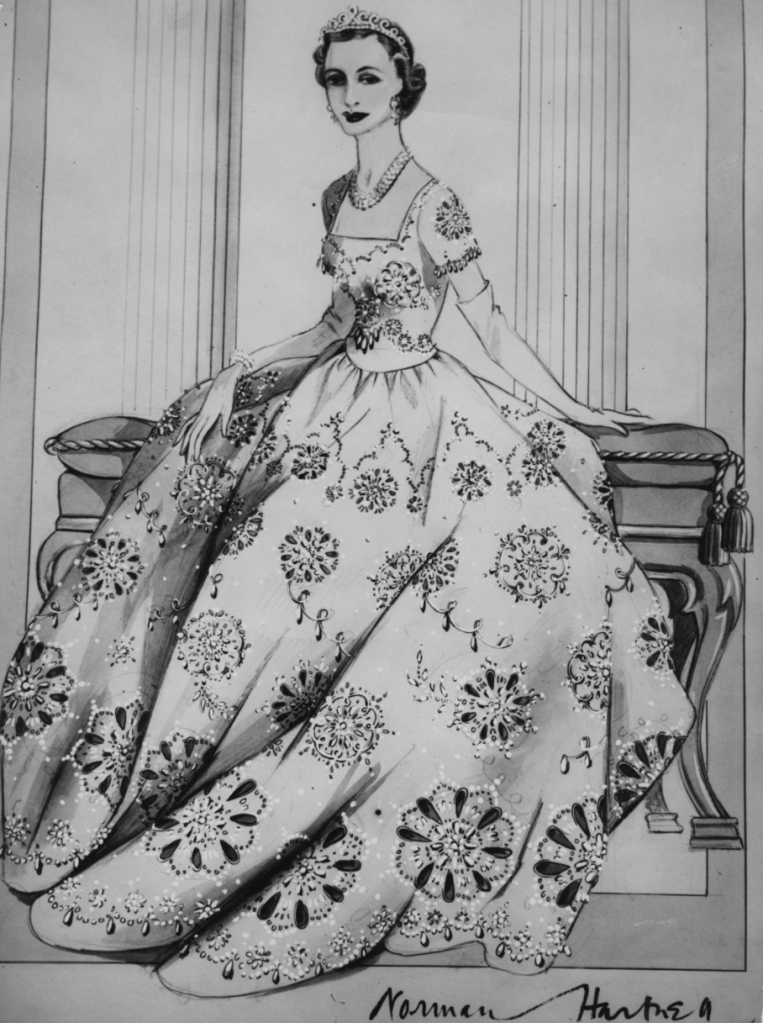

While the Queen’s coronation dress remains the most iconic, it was far from the only masterpiece unveiled that day. Sir Norman Hartnell, already revered within royal circles, was responsible for designing the gowns of all the principal female members of the Royal Family for the 1953 ceremony. Each gown was a visual statement tailored to its wearer and to the spirit of the occasion.

The Queen Mother

Rosie Harte, fashion historian and author of The Royal Wardrobe, describes the Queen Mother’s coronation gown as “a complete transformation from her simple 1930s gown.” During her time as consort, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon had embraced a romantic aesthetic – soft fabrics, gentle silhouettes, and an almost ethereal presence. Hartnell built on this image for the coronation, crafting a dramatic silk gown that elevated her image into that of a fairy-tale queen.

“Norman Hartnell created this dramatic silk gown to reinforce her whimsical image,” Harte explains, “but also to remind people who the outgoing Queen was. The design of the dress seems to peel open at the bottom to reveal a hem of sumptuous gold fabric.” The result was both nostalgic and majestic – a tribute to enduring royal glamour.

Princess Margaret

Princess Margaret’s gown struck a different note – fresh, feminine, and unashamedly youthful. While her sister’s gown was heavy with symbolism and history, Margaret’s was delicately personal. Hartnell embroidered her dress with roses and marguerite flowers, a nod to her full name: Margaret Rose.

“Girly and regal all at once,” said Harte. Her accessories reflected the same balance — Margaret wore the Cartier Halo Tiara, a dainty piece that would later be worn by Kate Middleton on her wedding day. Behind it, she wore a small coronet, signifying her royal status.

Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent

Another royal lady dressed by Hartnell was Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent. Her gown, like those of her royal peers, was made from white satin and adorned with embroidered panels, echoing the botanical themes present throughout the family’s ensembles. Her look was completed with striking jewels: the Kent Festoon Tiara, a diamond bow brooch, and a spectacular pair of girandole earrings – a true display of royal splendour.

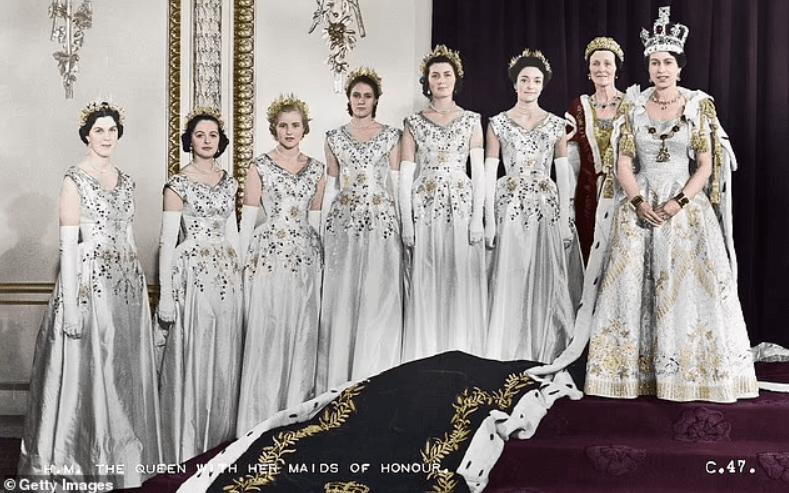

The Maids of Honour

To complement the grandeur of the Queen’s coronation ensemble, Hartnell also designed the gowns for the six Maids of Honour who attended the ceremony. These young noblewomen – Lady Moyra Hamilton, Lady Anne Coke, Lady Jane Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Lady Mary Baillie-Hamilton, Lady Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby, and Lady Rosemary Spencer-Churchill – played a pivotal role in the proceedings, assisting the Queen throughout the ceremony and carrying the train of her robes.

Their gowns, crafted from a pale peach silk satin, featured a gold leaf and pearl white blossom motif, cap sleeves and wide v-neck. There was intricate beaded decoration on the bodice, around the upper part of the skirt, and cascading down the back. The beadwork was exceptionally detailed, incorporating diamante, sequins, bugle beads, imitation pearls, and silver-painted leaves. To achieve the desired silhouette, the skirts included back pleats and attached wool wadding at the hips, providing structure and shape. These elements combined to create a cohesive and elegant visual accompaniment to the Queen’s own attire, highlighting Hartnell’s skill in creating a unified aesthetic.

The outfit worn by Lady Rosemary Spencer-Churchill was rediscovered in an attic at Blenheim Palace in recent years, and, following painstaking restoration by textile conservator Emma Telford, it was placed on display at the palace.

Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation was not only a moment of statecraft and tradition, but also a dazzling display of symbolism and craftsmanship. From the weight of the Queen’s own embroidered gown, to the thoughtful details sewn into the dresses of the royal women around her, every stitch spoke of history and legacy, whilst also symbolising the birth of a new reign. Over seventy years later, the garments still captivate, not only for their beauty, but for what they represent: a carefully fashioned image of monarchy, poised between duty and splendour.

Which of these royal gowns would you choose to wear – the Queen’s majestic silk and embroidery, Margaret’s floral femininity, or the romantic elegance of the Queen Mother? Let me know in the comments.